Policymakers, funders and organizations focus on survivors' safety to evaluate the effectiveness of domestic violence programs. We asked survivors how they define success and found a different answer.

The U.S. should be a country where everyone has a fair shot at opportunity, and to thrive. But let's be real: that's not the case. Watch this video to learn why — and how we can change it.

Full Frame Initiative partnered with community leaders to develop the Community Bill of Rights. This resource serves as a guide for government systems, philanthropy and nonprofits to center community, shift power and heal systemic harms.

All of us share a drive to feel whole, individually and collectively. We're all hardwired for wellbeing, and we all deserve a fair shot at it, too. But we don't all have the same access.

Use this tool to identify how a specific policy, project, program or practice will impact different stakeholders’ wellbeing, allowing you to anticipate and address unsustainable tradeoffs.

This is an example created for the St. Louis County Court (21st circuit) for an Investigation Summary Form Example that pays attention to wellbeing and tradeoffs.

FFI's CEO Katya Fels Smyth provides an overview of the Wellbeing Insights, Assets & Tradeoffs Tool (WIATT).

Understand how wellbeing and tradeoffs apply to a court hearing summary.

This is an example of how FFI worked with Missouri Children's Division to shift to using a welbeing framework at multiple levels.

This is a policy around professional development that pays attention to staff wellbeing and how staff wellbeing may also benefit the organization's goals.

These tools collect information from program participants in a refugee youth program and foster parents and staff.

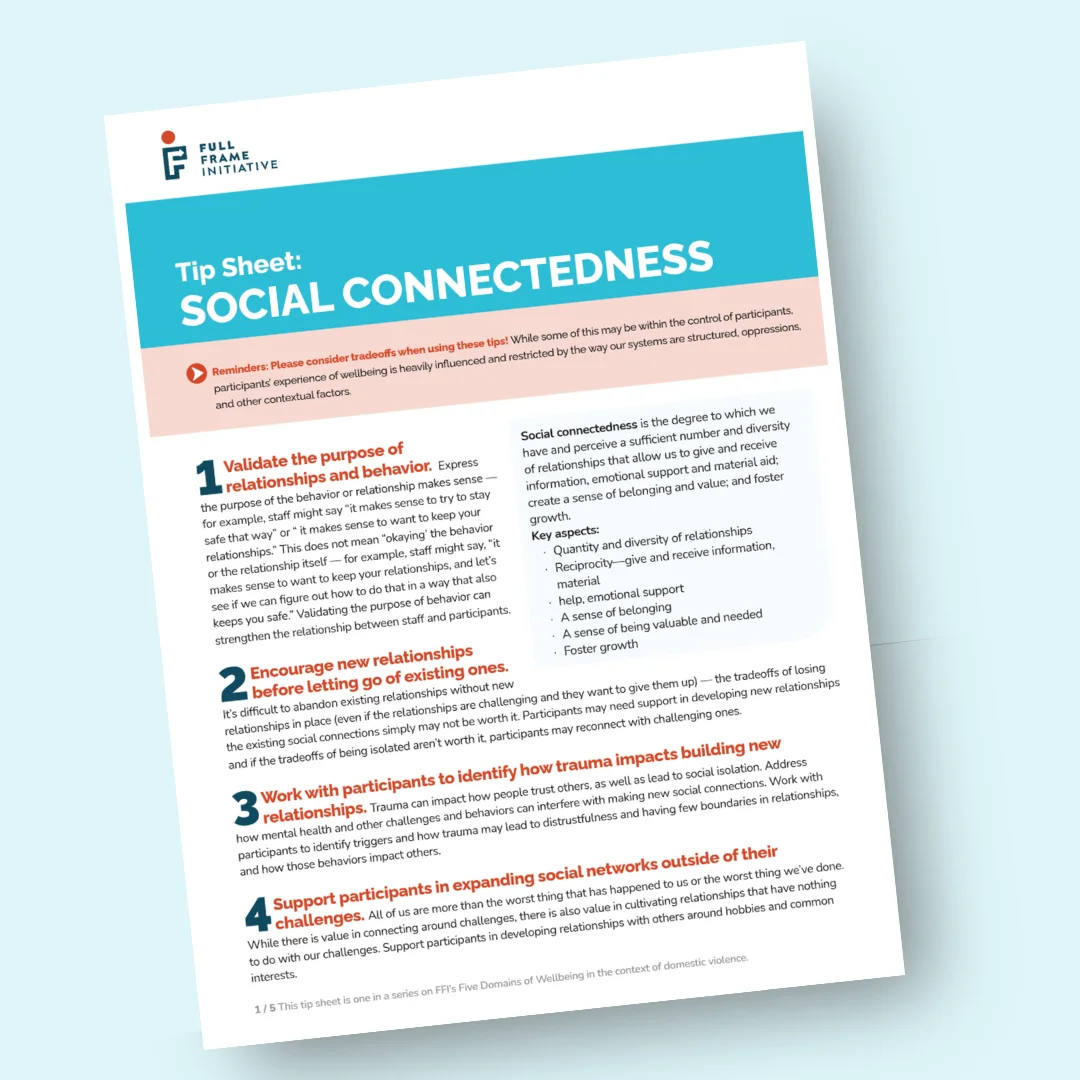

Download the tips sheet for definitions of each of the five domains of wellbeing and how to connect them to supporting survivors of domestic violence.